Paragraph Layout

Paragraph layout can also be complex and challenging. Some scripts do not break paragraphs as in the Latin script. For example, ancient Ethiopic uses a paragraph separator mark (፨) rather than beginning the next paragraph on a new line.

Baseline

Section titled “Baseline”Baselines can also vary. This will affect line spacing (otherwise known as leading) as well as the space above and below paragraphs. When the baseline is sloping, the height of a word grows as the length of the word increases. This is especially challenging in setting the linespacing. Some examples:

Underlining

Section titled “Underlining”The type of baseline will also affect underlining of text. If the baseline is hanging or sloping what is the best way to underline that text? One would need to study conventions used with each script.

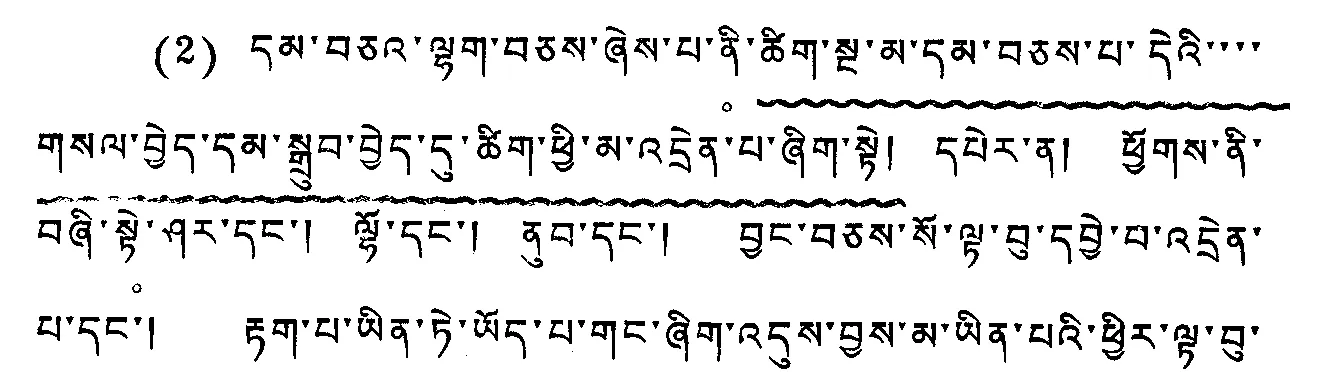

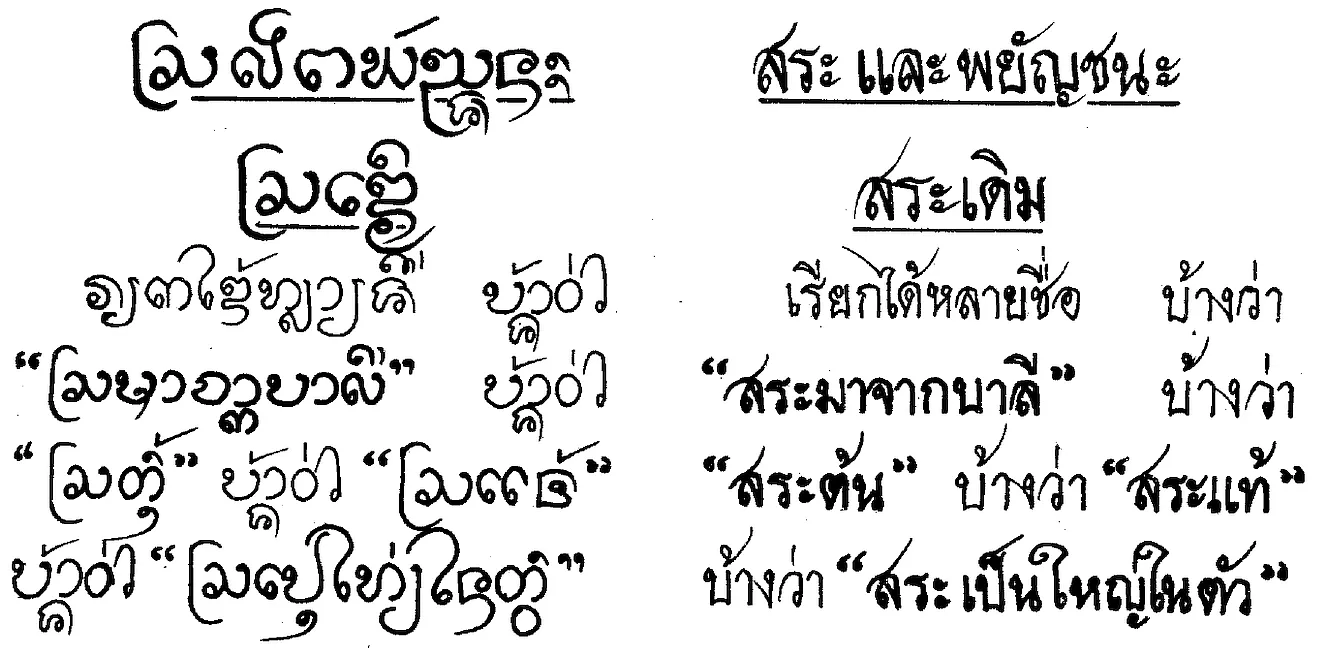

In the Tibetan example in Figure 1, there appears to be a wavy underline almost as far down as the top of the next line. Without knowing the rules of the writing system one cannot know the purpose of it. The small circles under several of the glyphs actually represent something similar to underlining in Latin typography, thus the wavy underline most likely represents some other form of emphasis. It is important to check this out rather than making assumptions based on design guidelines one is most familiar with. Figure 2 shows another example of underlining. One can see in both the Lanna (left) and Thai (right) titles the underline does not cross the descenders. Although technically more difficult, this is more aesthetically appealing than if the underline crossed the descenders or was set below them.

Mixed direction

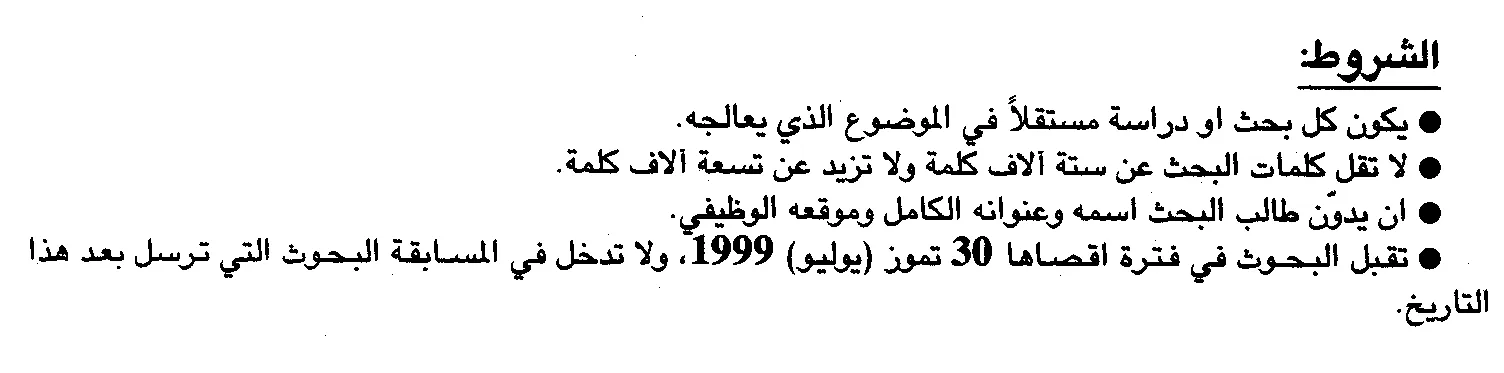

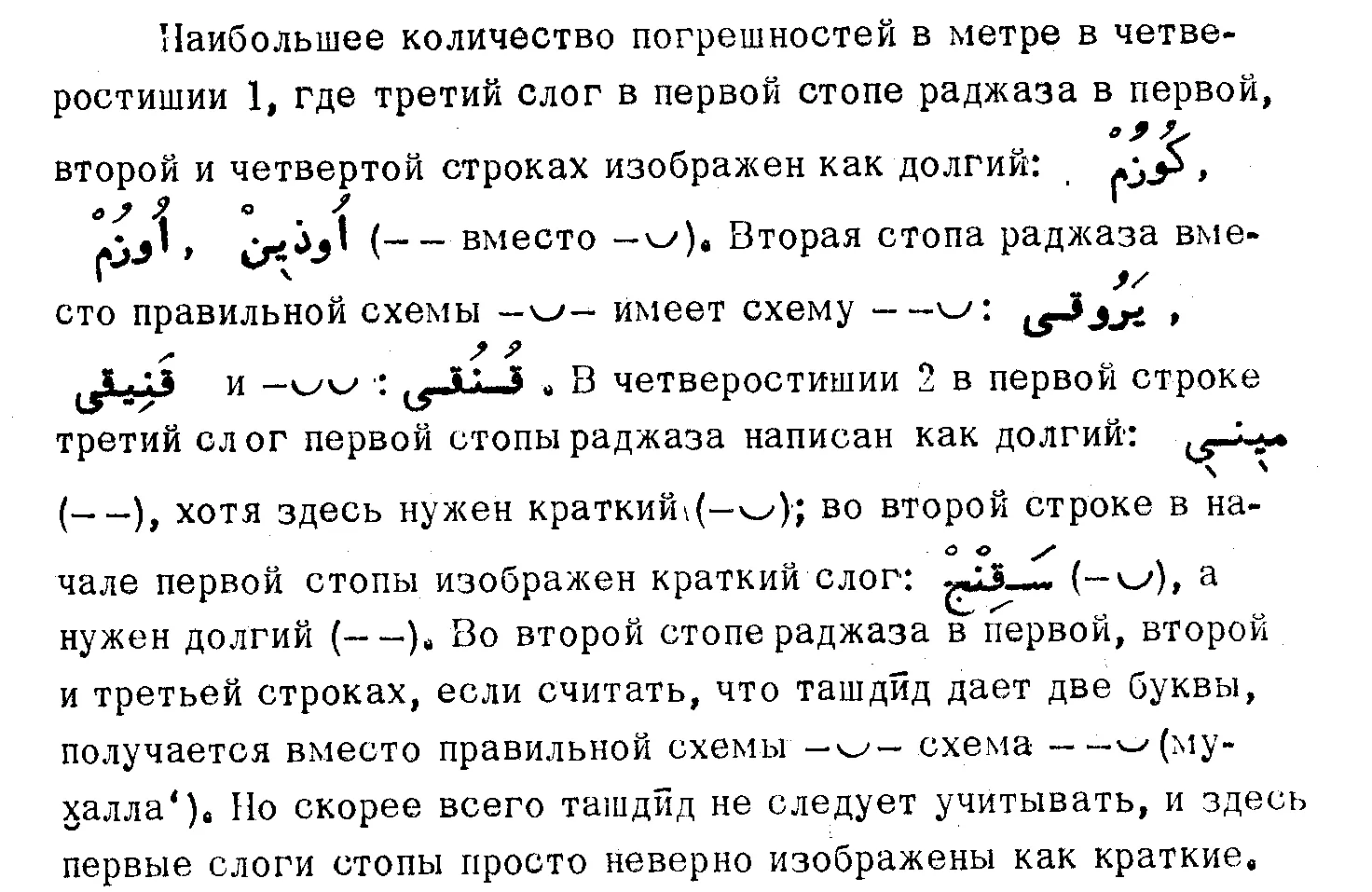

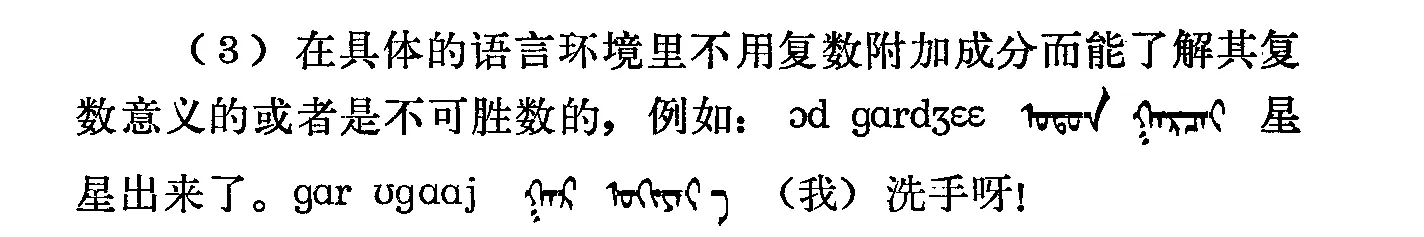

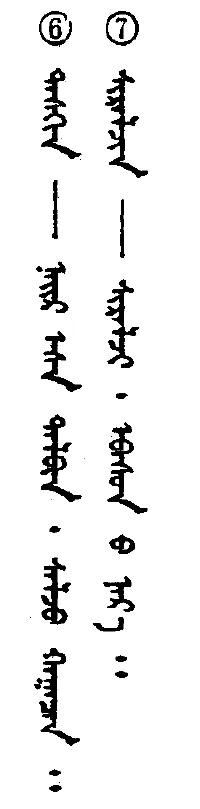

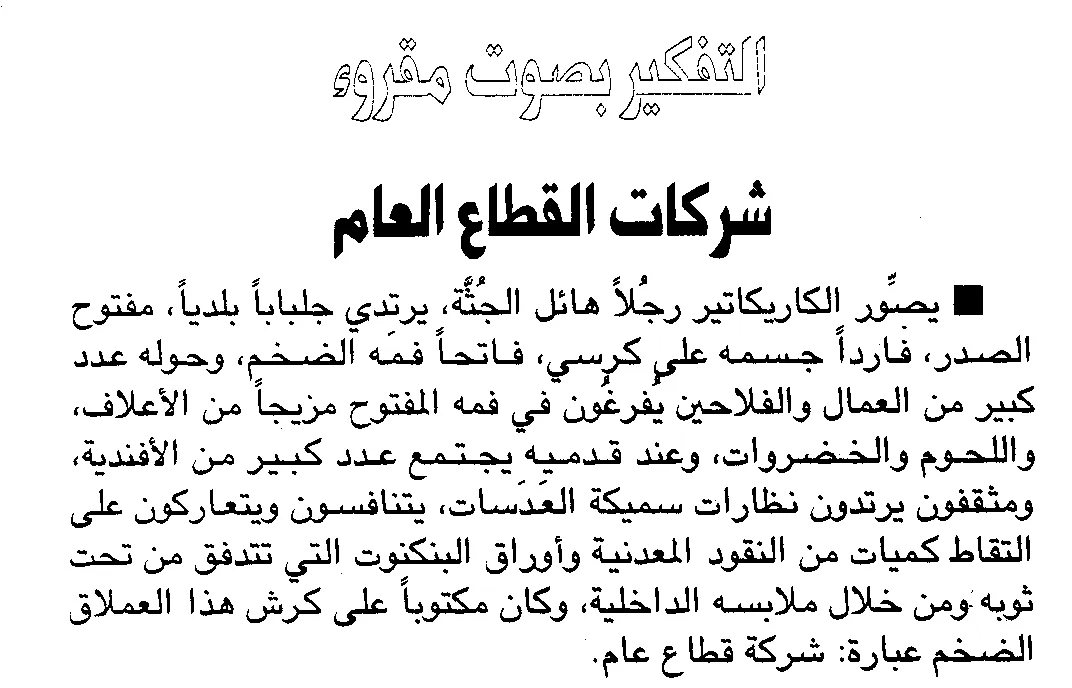

Section titled “Mixed direction”Mixed direction text can be especially interesting. LTR behavior of numbers in Arabic text is seen in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows justification problems the application had when RTL text was at the beginning of a LTR line (but at the end of the RTL text – note the undesirable extra white space at the left edge of lines 4 and 6 and at the right edge of lines 3 and 5). Figure 5 illustrates how Latin script text is set vertically with Mongolian. It appears to be standard in Chinese, Japanese and Mongolian to rotate the Latin script text 90 degrees rather than stack letters vertically. There are texts which are stacked rather than rotated but these are generally only with very short runs of Latin text (3-4 glyphs).

When set horizontally, Chinese is typically LTR as seen in Figure 6, but Figure 7 has Chinese set RTL as a result of the RTL behavior of Qazaq, written with Arabic script. A Chinese text which is set LTR with IPA and Mongolian “in line” is seen in Figure 8.

Bullets and Indents

Section titled “Bullets and Indents”RTL behavior needs to be properly implemented with regards to bullets (see Figure 9) and paragraph indents (see Figure 11). Vertical scripts also need proper bullets (see Figure 10) and paragraph indenting. As with any formatting decisions, the typesetter needs to examine a great variety of examples to see what is considered normal and beautiful. The typesetter who comes from a Roman perspective to typeset Arabic would probably choose to use smaller bullets than those used in Figure 9, but the larger bullets might be considered beautiful to readers of Arabic.

Verse numbers

Section titled “Verse numbers”In Christian biblical typesetting, there is the question of how to display verse numbers. There are three main approaches:

- Inline verse numbers insert the verse number, usually as a superscript number, before the text in the verse.

- Marginal verse numbers move the verse numbers out into the margin.

- Hanging verse numbers hang them off the following text.

The last two of these approaches deserve additional description.

“Marginal” verse numbers

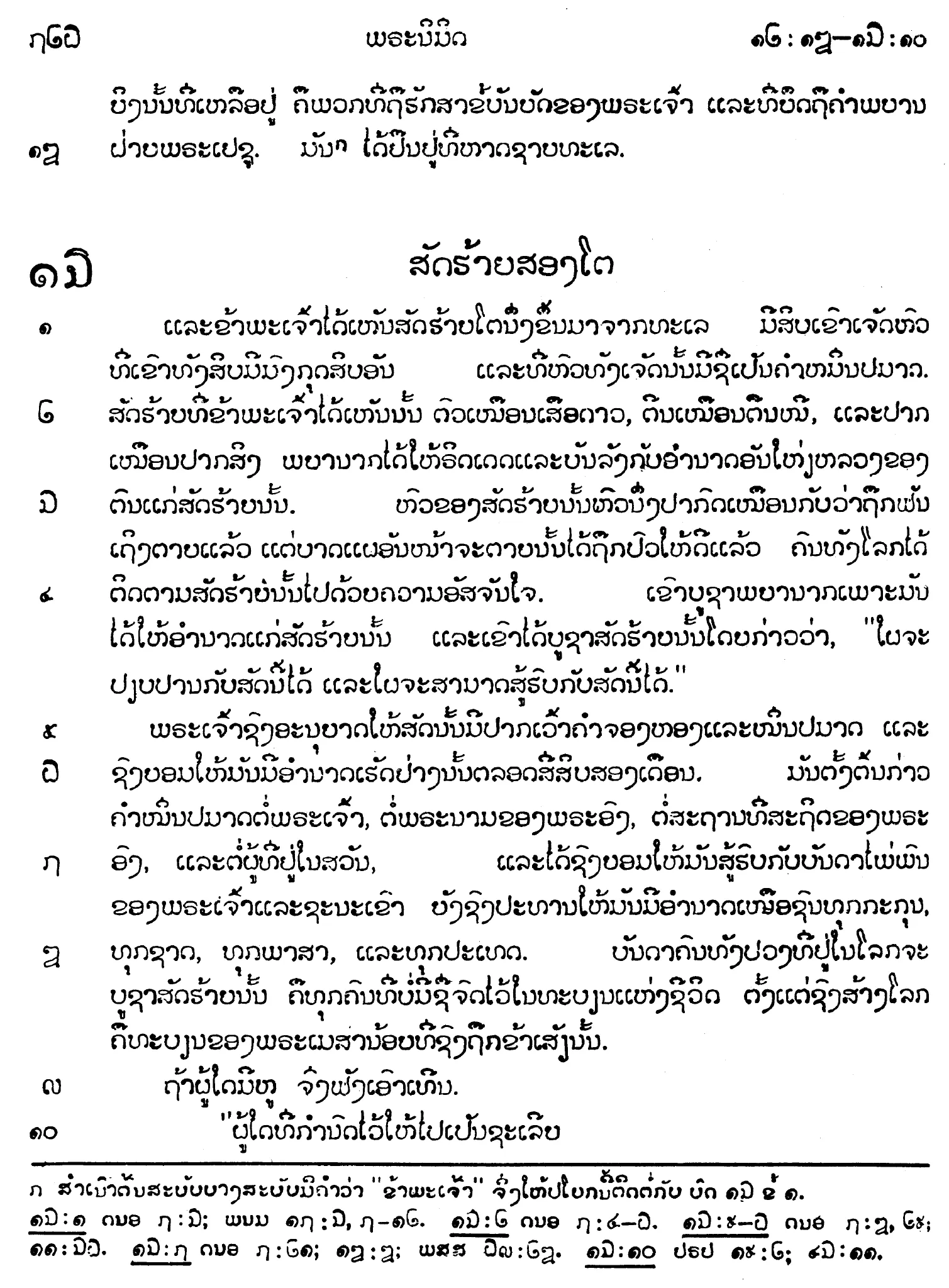

Section titled ““Marginal” verse numbers”It is fairly unusual to see “marginal” verse numbers in Latin script scriptures today. They are common in other scripts. Marginal verse numbers are never easy to implement. The Lao New Testament in Figure 12 uses hanging chapter and verse numbers (which appear down the far left of the page). Another instance of hanging verse numbers is seen in Figure 13 (the small digits at the top of the page).

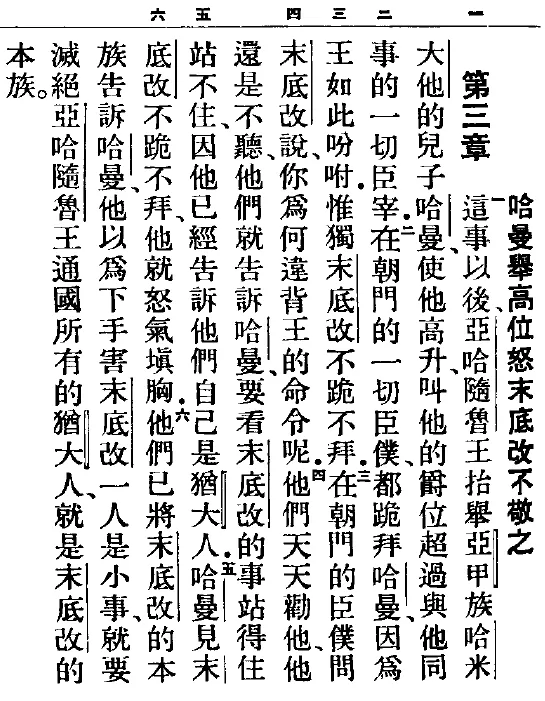

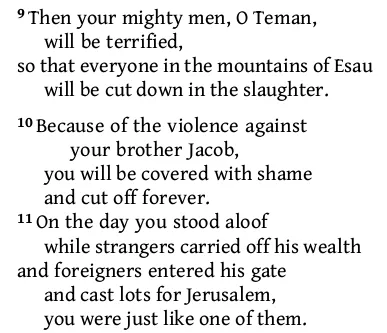

“Hanging” verse numbers

Section titled ““Hanging” verse numbers”Hanging verse numbers are often used in poetry contexts where the position of the start of the text is fixed and the verse numbers hangs off to the left (in LTR text) and may be of variable width. In the two examples below compare the position of the start of each line of text and the start of the verse number.

Figures

Section titled “Figures”- China Tibetan Language Department Higher Buddhist Studies Institute (ed.) 1987. Work said to be the key to open the door of snowland wisdom. Book 1, p. 24. Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House.

- Phayomyong, Manee. 2533 (Buddhist calendar). Learning to Read Lanna Thai (translation), p. 1. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Chiang Mai University. Printed by Sap Karn Pim.

- .15 June, 1999. Al Hayat Newspaper. Issue No 13247 p. 2.

- Stebleva, I.V. 1971. The Development of Turkic Poetic Forms in the Eleventh Century, p. 37. Moscow: Nauka. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Institute of Oriental Studies.

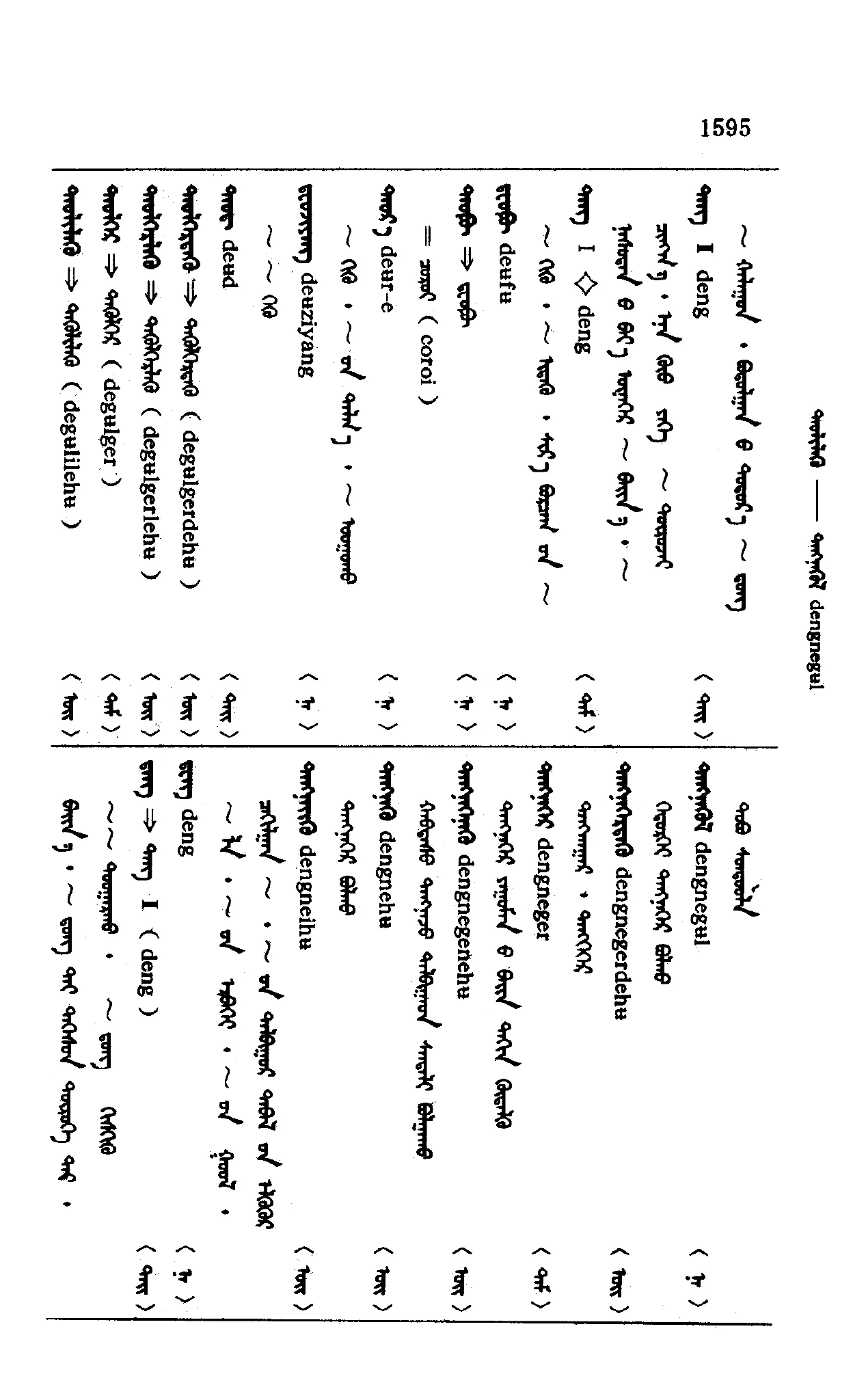

- .1999. Mongol zuv bichgiin toli (dictionary), p. 1595. Inner Mongolian Newspaper Publication Agency, Inner Mongolian People’s Publication Committee, Inner Mongolian national Printing house.

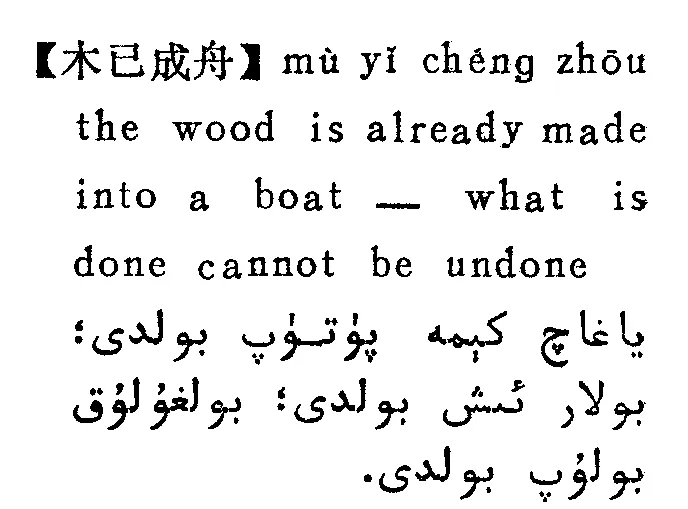

- Qawuz, Qadir. 1990. Hanzučä, Ingliz čä Uyghur čä turaqluq ibarilar lughati. (Chinese-English-Uighur Dictionary of Idioms), p. 504. Urumqi: Xinjiang Minzu Chubanshe.

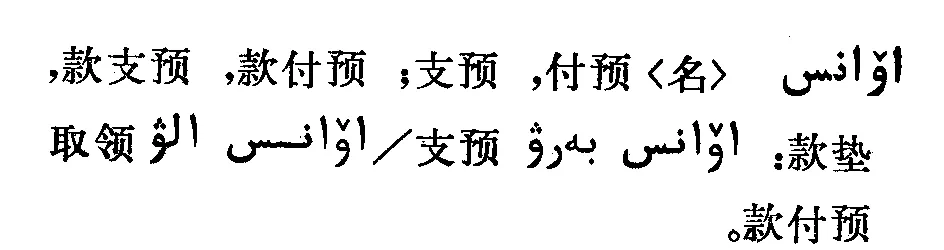

- Nurbek. Chief editor. 1989. Ha-Han Cidian: Qazaq Xansushu Sözdik (Chinese-Qazak Dictionary), p. 4. Beijing: Minzu Chubanshe.

- Surizhu. 1985. Mengguyu wenji (Anthology of Mongolian languages), p. 124. Xining: Qinghai People’s Publishing House.

- .15 June, 1999. Al Hayat Newspaper. Issue No 13247 p. 2.

- G. Buyanbat. 1985. Mongoliin ertnii bilig surgal, p. 91. Inner Mongolia: Inner Mongolian People’s Publication Committee.

- .15 June, 1999. Al Hayat Newspaper. Issue No 13247 p. 23.

- .1981. Lao New Testament, p. 726. KBS.

- .1982. Bible in Chinese Union Version, “Shangti” Edition 2546, p. 619. Hong Kong: The Bible Society in Hong Kong.

Portions of this content first appeared in Implementing Writing Systems, copyright © 2001 SIL International.