Unicode Concepts

Encoding refers to the process of representing information in some form. In computer systems, we encode written language by representing the graphemes or other text elements of the writing system in terms of sequences of characters, units of textual information within some system for representing written texts. These characters are in turn represented within a computer in terms of the only means of representation the computer knows how to work with: binary numbers.

A character set encoding (or character encoding) is such a system for doing this. Any character set encoding involves at least these two components: a set of characters and some system for representing these in terms of the processing units used within the computer.

Unicode is a standard encoding designed to be a universal character set that covers all of the scripts in the world. The parallel ISO/IEC 10646 standard specifies the Universal Coded Character Set (UCS). It is intended to have the exact repertoire as is in The Unicode Standard (TUS).

Codepoints and the Unicode codespace

Section titled “Codepoints and the Unicode codespace”The Unicode coded character set is coded in terms of integer values, which are referred to in Unicode as Unicode scalar values (USVs). By convention, Unicode codepoints are represented in hexadecimal notation with a minimum of four digits and preceded with “U+”; so, for example, “U+0345”, “U+10345”, and “U+20345”. Also by convention, any leading zeroes above four digits are suppressed; thus we would write “U+0456” but not “U+03456”.

Every character in Unicode can be uniquely identified by its codepoint, or also by its name. Unicode character names use only ASCII characters and by convention are written entirely in upper case. Characters are often referred to using both the codepoint and the name; e.g. U+0061 LATIN SMALL LETTER A. In discussions where the actual characters are unimportant or are assumed to be recognizable using only the codepoints, people will often save space and use only the codepoints. Also, in informal contexts where it is clear that Unicode codepoints are involved, people will often suppress the string “U+”. For clarity, this document will continue to use “U+”.

The Unicode codespace ranges from U+0000 to U+10FFFF. Borrowing terminology from ISO/IEC 10646, the codespace is described in terms of 17 planes of 64K codepoints each. Thus, Plane 0 includes codepoints U+0000..U+FFFF, Plane 1 includes codepoints U+10000..U+1FFFF, etc.

In the original design of Unicode, all characters were to have codepoints in the range U+0000..U+FFFF. In keeping with this, Plane 0 was set apart as the portion of the codespace in which all of the most commonly used characters were encoded, and is designated the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP). The remainder of the codespace, Planes 1 to 16, are referred to collectively as the Supplementary Planes. As space ran out in the BMP, not only ancient scripts, but modern characters and scripts have been encoded in the Supplementary Multilingual Plane (SMP).

There are gaps in the Unicode codespace: codepoints that are permanently unassigned and reserved as non-characters. These include the last two codepoints in each plane, U+nFFFE and U+nFFFF (where n ranges from 0 to 1016). These have always been reserved, and characters will never be assigned at these codepoints. One implication of this is that these codepoints are available to software developers to use for proprietary purposes in internal processing. Note, however, that care must be taken not to transmit these codepoints externally.

Unassigned codepoints can be reserved in a similar manner at any time if there is a reason for doing so. This has been done specifically in order to make additional codes available to programmers to use for internal processing purposes. Again, these should never appear in data.

Surrogates

Section titled “Surrogates”There is another special range of 2,048 codepoints that are reserved, creating an effective gap in the codespace. These occupy the range U+D800..U+DFFF and are reserved due to the mechanism used in the UTF-16 encoding form (see Chapter 2 of the Unicode Standard). In UTF-16, codepoints in the BMP are represented as code units having the same integer value. The code units in the range 0xD800–0xDFFF, serve a special purpose, however. These code units, known as surrogate code units (or simply surrogates), are used in representing codepoints from Planes 1 to 16. As a result, it is not possible to represent the corresponding codepoints in UTF-16. Hence, these codepoints are reserved.

Blocks & Extensions

Section titled “Blocks & Extensions”As mentioned above, the Basic Multilingual Plane is intended for those characters that are most commonly used. This implies that the BMP is primarily for scripts that are currently in use, and that other planes are primarily for scripts that are not in current use. This is no longer completely true. As the BMP has filled up, the SMP is also used for modern scripts.

As development of Unicode began, characters were first taken from existing industry standards. For the most part, those included characters used in writing modern languages, but also included a number of commonly used symbols. As these characters were assigned, they were added to the BMP. Assignments to the BMP were done in an organized manner, with some allowances for possible future additions.

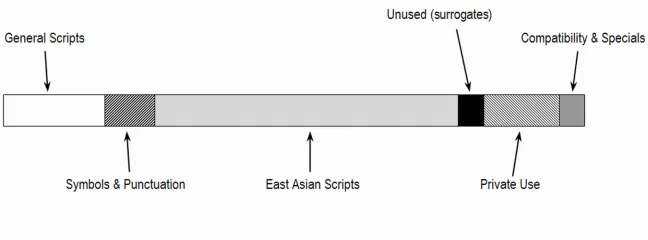

The overall organization of the BMP is illustrated below.

There are a couple of things to note straight away. Firstly, note the range of unused codepoints. This is the range U+D800..U+DFFF that is reserved to allow for the surrogates mechanism in UTF-16, as mentioned in the section above.

Secondly, note the range of codepoints designated “Private Use”. This is a block of codepoints called the Private Use Area (PUA). These codepoints are permanently unassigned, and are available for custom use by users or vendors. This occupies the range U+E000..U+F8FF, giving a total of 6,400 private-use codepoints in the BMP. In addition, the last two planes, Plane 15 and Plane 16, are reserved for private use, giving an additional 131,068 codepoints. Thus, there are a total of 137,468 private-use codepoints that are available for private definition. These codepoints will never be given any fixed meaning in Unicode. Any meaning is purely by individual agreement between a sender and a receiver or within a given group of users.

Let us briefly outline the organization of the supplementary planes. As just mentioned, Planes 15 and 16 are set aside for private use. Prior to TUS 3.1, no character assignments had been made in the supplementary planes. Beginning with TUS 3.1, however, a number of characters were assigned to Planes 1, 2 and 14. Plane 1 contains modern scripts, characters that were required for scripts in the BMP and for which there is no more space in the BMP, scripts that are no longer in use, and for large sets of symbols used in particular fields, such as music and mathematics. Plane 2 is set aside for additional Han Chinese characters. Plane 14 is designated for special-purpose characters; for example, characters that are required for use only in certain communications protocols.

In any of the planes, characters are assigned in named ranges referred to as blocks. Each block occupies a contiguous range of codepoints, and generally contains characters that are somehow related. Typically, a block contains characters for a given script. For example, the Thaana block occupies the range U+0780..U+07BF and contains all of the characters of the Thaana script.

The Unicode Standard includes a collection of data files that provide detailed information about semantic properties of characters in the Standard that are needed for implementations. These data files are always available from the Unicode Web site. These can be found online: Unicode Character Database. Further information on the data files is also available on the Unicode web site.

One of these data files, Blocks.txt, lists all of the assigned blocks in Unicode, giving the name and range for each.

While a given language may be written using a script for which there is a named block in Unicode, that block may not contain all of the characters needed for writing that language. Some of the characters for that language’s writing system may be found in other blocks. For example, there are six Cyrillic blocks (U+0400..U+04FF, U+0500..U+052F, U+2DE0..U+2DFF, U+A640..U+A69F, U+1C80..U+1C8F, U+1E030..U+1E08F). However, those blocks do not contain most of the punctuation characters required for writing in Cyrillic. The writing system for a language such as Russian will require punctuation characters in the Basic Latin block (U+0020..U+007F) as well as the General Punctuation block (U+2000..U+206F).

Also, the characters for some scripts are distributed between two or more blocks. For example, the Basic Latin block (U+0020..U+007F) and the Latin 1 Supplement block (U+00A0..U+00FF) were assigned as separate blocks because of the relationship each has to source legacy character sets. There are many other blocks also containing Latin characters. Thus, if you are working with a writing system based on Latin script, you may need to become familiar with all of these various blocks. Fortunately, only a limited number of scripts are broken up among multiple blocks in this manner. There is also a data file, Scripts.txt, which identifies exactly which Unicode codepoints are associated with each script. The format and contents of this file are described in UAX #24. You are best off simply familiarizing yourself with the character blocks in the Unicode character set, but if you need some help, these files are available.

The Unicode Standard gives a layout of all of the blocks and scripts in the BMP as well as a similar layout for the existing (and projected) blocks and scripts in the SMP. Clicking on a particular block will take the user to the code chart for that particular block (or where the script is not encoded yet, the link will take you to the most recent Unicode proposal). (Note that there are a large number of additional Han ideographs in Plane 2.) In addition, there are a number of blocks containing various dingbats and symbols, such as arrows, box-drawing characters, mathematical operators and Braille patterns. Apart from the Braille patterns, most symbols were taken from various source legacy standards.

The Unicode Core Specification contains individual chapters that describe groups of related scripts. For example, Chapters 12-15 discuss scripts of South and Central Asia. If you need to learn how to implement support for a given script using Unicode, then the relevant chapter in the Standard for that script is essential reading.

Unicode characters and code charts

Section titled “Unicode characters and code charts”In addition to the chapters in the Standard that describe different scripts, the Standard also contains a complete set of code charts, organized by block. The best way to learn about the characters in the Unicode Standard is to read the Standard and browse through its charts.

The Character Code Charts are available online. The code charts include tables of characters organized in columns of 16 rows. The column headings show all but the last hexadecimal digit of the USVs; thus, the column labelled “21D” shows glyphs for characters U+21D0..U+21DF. Within the charts, combining marks are shown with a dotted circle that represents a base character with which the mark would combine (as explained at the start of this paper). Also, unassigned codepoints are indicated by table cells that are shaded in grey or that have a diagonal lined pattern fill.

The regular code charts are organized in the numerical order of Unicode scalar values. There are also various other charts available online that are organized in different orders. In particular, there are a set of charts available in UAX #24 that show all characters from all blocks for a given script, sorted in a default collating order. This can provide a useful way to find characters that you are looking for. Note that these other charts do not necessarily use the same presentation as the regular code charts, such as using tables with 16 rows. Also, you will probably find it helpful to use both these charts that are organized by scripts as well as the regular charts that are organized by blocks. Because the text describing characters and scripts and the code charts in the Standard itself are organized around blocks, it is important that you not only become familiar with the individual characters used in the writing systems that you work with but also with the blocks in which they are located.

Each of the regular code charts is accompanied by one or more pages of supporting information that is known as the names list. The names list includes certain useful information regarding each character. This includes some of the normative character properties, specifically the character name and the canonical or compatibility decompositions. In addition, it includes a representative glyph for each character as well as some additional notes that provide some explanation as to what this character is and how it is intended to be used.

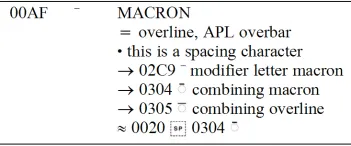

If you take a quick glance at the names list, you will quickly note that certain special symbols are used. The organization and presentation of the names list is fully explained in the introduction to Chapter 24. As a convenience, we will briefly describe the meaning of some of the symbols. To illustrate, let us consider a sample entry:

This example is useful as it contains each of the different types of basic elements that may be found in a names list entry.

The first line of an entry always shows the Unicode scalar value (without the prefix “U+”), the representative glyph, and the character name.

If a character is also known by other names, these are given next on lines beginning with the equal sign “=”. If there are multiple aliases, they will appear one per line. These are generally given in lower case. In some cases, they will appear in all caps; that indicates that the alternate name was the name used in TUS 1.0, prior to the merger with ISO/IEC 10646.

Lines beginning with bullets “·” are informative notes. Generally, these are added to clarify the identity of the character. For example, the note shown above helps to prevent confusion with an over-striking (combining) macron. Informative notes may also be added to point out special properties or behaviour, such as a case mapping that might otherwise not have been expected. Notes are also often added to indicate particular languages for which the given character is used.

Lines that begin with arrows “→” are cross-references. The most common purpose of cross-references is to highlight distinct characters with which the given character might easily be confused. For example, U+00AF is similar in appearance to U+02C9, but the two are distinct. Another use of cross-references is to point to other characters that are in some linguistic relationship with the given character, such as the other member of a case pair (see, for instance, U+0272 ɲ LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH LEFT HOOK), or a transliteration (see, for instance, U+045A њ CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER NJE).

Lines that begin with an equivalence sign “≡” or an approximate equality sign “≈” are used to indicate canonical and compatibility decompositions respectively.

The complete NamesList.txt is available online as an ASCII-encoded plain text file (without representative glyphs for characters). The format used for this file is documented at NamesList File Format.

As you look through the code charts and the names list, bear in mind that this is not all of the information that the Standard provides about characters. It is just a limited amount that is generally adequate to establish the identity of each character. That is the main purpose they are intended for. If you need to know more about the intended use and behaviour of a particular character, you should read the section that describes the particular block containing that character (Chapters 7–20 of TUS Core Specification), and also check the semantic character properties for that character in the relevant parts of the Standard.

There are additional things you need to know in order to work with the characters in Unicode, particularly if you are trying to determine how the writing-system of a lesser-known language should be represented in Unicode. Before we look further at the details of the Unicode character set, however, we will explore the various encoding forms and encoding schemes used in Unicode.

Transformation Formats

Section titled “Transformation Formats”All text should be read and interpreted according to the proper encoding and transformation format.

There are three main encoding forms that are part of Unicode: UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32. This section describes these forms, however, explicit specifications are provided in Appendix A: Mapping codepoints to Unicode encoding forms. There are also two alternative encoding forms used for ISO/IEC 10646, each with relative merits. Finally, this section covers various encoding schemes defined as part of Unicode and the mechanism provided for resolving byte-order issues.

UTF-16

Section titled “UTF-16”Because of the early history of Unicode and the original design goal to have a uniform 16-bit encoding, many people today think of Unicode as a 16-bit-only encoding. This is so even though Unicode now supports three different encoding forms, none of which is, in general, given preference over the others. UTF-16 might be considered to have a special importance, though, precisely because it is the encoding form that matches popular impressions regarding Unicode.

The original design goal of representing all characters using exactly 16 bits had two benefits. First it made processing efficient since every character was exactly the same size, and there were never any special states or escape sequences. Secondly, it made the mapping between codepoints in the coded character set and code units in the encoding form trivial: each character would be encoded using the 16-bit integer that is equal to its Unicode scalar value. Although it is no longer possible to maintain this fully in the general case, there would still be some benefit it this could be maintained in common cases. UTF-16 does this.

As mentioned earlier, the characters that are most commonly used, on average, are encoded in the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP). Thus, for many texts it is never necessary to refer to characters above U+FFFF. If a 16-bit encoding form were used in which characters in the range U+0000..U+FFFF were encoded as 16-bit integers that matched their scalar values, this would work for such texts, but fail if any supplementary-plane characters occurred. If, however, some of the codepoints in that range were permanently reserved, perhaps they could somehow be used in some scheme to encode characters in the supplementary planes. This is precisely the purpose of the surrogate code units in the range 0xD800–0xDFFF.

The surrogate range covers 2,048 code values. UTF-16 divides these into two halves: 0xD800–0xDBFF are called high surrogates; 0xDC00–0xDFFF are called low surrogates. With 1,024 code values in each of these two sub-ranges, there are 1,024 x 1,024 = 1,048,576 possible combinations. This matches exactly the number of codepoints in the supplementary planes. Thus, in UTF-16, a pair of high and low surrogate code values, known as a surrogate pair, is used in this way to encode characters in the supplementary planes. Characters in the BMP are directly encoded in terms of their own 16-bit values.

So, UTF-16 is a 16-bit encoding form that encodes characters either as a single 16-bit code unit or as a pair of 16-bit code units, as follows:

| Codepoint range | Number of UTF-16 code units per codepoint |

|---|---|

| U+0000..U+D7F | one |

| U+D800..U+DFFF | none (reserved—no characters assignable) |

| U+E000..U+FFFF | one |

| U+10000..U+10FFFF | two: one high surrogate followed by one low surrogate |

It should be pointed out that a surrogate pair must consist of a high surrogate followed by a low surrogate. If an unpaired high or low surrogate is encountered in data, it is considered ill-formed, and must not be interpreted as a character.

The calculation for converting from the code values for a surrogate pair to the Unicode scalar value of the character being represented is described in Appendix A: Mapping codepoints to Unicode encoding forms.

One of the purposes of Unicode was to make things simpler than the existing situation with legacy encodings such as the multi-byte encodings used for Far East languages. On learning that UTF-16 uses either one or two 16-bit code units, many people ask how this is any different from what was done before. There is a very significant difference in this regard between UTF-16 and legacy encodings. In the older encodings, the meaning of a code unit could be ambiguous. For example, a byte 0x73 by itself might represent the character U+0073, but it might also be the second byte in a two-byte sequence 0xA4 0x73 representing the Traditional Chinese character 山 ‘mountain’.

In order to determine what the correct interpretation of this byte should be, it is necessary to backtrack in the data stream, possibly all the way to the beginning. In contrast, the interpretation of code units in UTF-16 is never ambiguous: when a process inspects a code unit, it is immediately clear whether the code unit is a high or low surrogate. In the worst case, if the code unit is a low surrogate, the process will need to back up one code unit to get a complete surrogate pair before it can interpret the data.

The UTF-8 encoding form was developed to work with existing software implementations that were designed for processing 8-bit text data. In particular, it had to work with file systems in which certain byte values had special significance. (For example, 0x2A, which is “*” in ASCII, is typically used to indicate a wildcard character). It also had to work in communication systems that assumed bytes in the range 0x00 to 0x7F (especially the control characters) were defined in conformance to certain existing standards derived from ASCII. In other words, it was necessary for Unicode characters that are also in ASCII to be encoded exactly as they would be in ASCII using code units 0x00 to 0x7F, and that those code units should never be used in the representation of any other characters.

UTF-8 uses byte sequences of one to four bytes to represent the entire Unicode codespace. The number of bytes required depends upon the range in which a codepoint lies.

The details of the mapping between codepoints and the code units that represent them is described in Appendix A: Mapping codepoints to Unicode encoding forms. An examination of that mapping reveals certain interesting properties of UTF-8 code units and sequences. Firstly, sequence-initial bytes and the non-initial bytes come from different ranges of possible values. Thus, you can immediately determine whether a UTF-8 code unit is an initial byte in a sequence or is a following byte. Secondly, the first byte in a UTF-8 sequence provides a clear indication, based on its range, as to how long the sequence is.

These two characteristics combine to make processing of UTF-8 sequences very efficient. As with UTF-16, this encoding form is far more efficient than the various legacy multi-byte encodings. The meaning of a code unit is always clear: you always know if it is a sequence-initial byte or a following byte, and you never have to backup more than three bytes in the data in order to interpret a character.

Another interesting by-product of the way UTF-8 is specified is that ASCII-encoded data automatically also conforms to UTF-8.

It should be noted that the mapping from codepoints to 8-bit code units used for UTF-8 could be misapplied so as to give more than one possible representation for a given character. The UTF-8 specification clearly limits which representations are legal and valid, however, allowing only the shortest representation. This matter is described in detail in Appendix A: Mapping codepoints to Unicode encoding forms.

UTF-32

Section titled “UTF-32”The UTF-32 encoding form is very simple to explain: every codepoint is encoded using a 32-bit integer equal to the scalar value of the codepoint. This is described further in Appendix A: Mapping codepoints to Unicode encoding forms.

ISO/IEC 10646 encoding forms: UCS-4 and UCS-2

Section titled “ISO/IEC 10646 encoding forms: UCS-4 and UCS-2”It is also useful to know about two additional encoding forms that are allowed in ISO/IEC 10646. UCS-4 is a 32-bit encoding form that supports the entire 31-bit codespace of ISO/IEC 10646. It is effectively equivalent to UTF-32, except with respect to the codespace: by definition UCS-4 can represent codepoints in the range U+0000..U+7FFFFFFF (the entire ISO/IEC 10646 codespace), whereas UTF-32 can represent only codepoints in the range U+0000..U+10FFFF (the entire Unicode codespace).

UCS-2 is a 16-bit encoding form that can be used to encode only the Basic Multilingual Plane. It is essentially equivalent to UTF-16 but without surrogate pairs, and is comparable to what was available in TUS 1.1. References to UCS-2 are much less frequently encountered than was true in the past. You may still come across the term, though, so it is helpful to know. Also, it can be useful in describing the level of support for Unicode that certain software products may provide.

Further resource: A Code Converter that enables online comparison of formats

Principles & Compromises

Section titled “Principles & Compromises”Which encoding is the right choice?

Section titled “Which encoding is the right choice?”With three different encoding forms available, someone creating content is faced with the choice of which encoding they should use for the data they create. Likewise, software developers need to consider this question both for what they use as the internal memory representation of data and what they use when storing data on a disk or transmitting it over a wire. The answer depends on a variety of factors, including the nature of the data, the nature of the processing, and the contexts in which it will be used.

One of the original concerns people had regarding Unicode was that a 16-bit encoding form would automatically double file sizes in relation to an 8-bit encoding form. Unicode’s three encoding forms do differ in terms of their space efficiency, though the actual impact depends upon the range of characters being used and on the proportions of characters from different ranges within the codespace. Consider the following:

| Codepoint range | Number of bytes: UTF-8 | Number of bytes: UTF-16 | Number of bytes: UTF-32 |

|---|---|---|---|

| U+0000..U+007F | one | two | four |

| U+0080..U+07FF | two | two | four |

| U+0800..U+D7FF, U+E000..U+FFFF | three | two | four |

| U+10000..U+10FFFF | four | four | four |

Table 1: Bytes required to represent a character in each encoding form

Clearly, UTF-32 is less efficient, unless a large proportion of characters in the data come from the supplementary planes, which is usually not likely. (For supplementary-plane characters, all three encoding forms are equal, requiring four bytes.) For characters in the Basic Latin block of Unicode (equivalent to the ASCII character set), i.e. U+0000..U+007F, UTF-8 is clearly the most efficient. On the other hand, for characters in the BMP used for Far East languages, UTF-8 is less efficient than UTF-16.

Another factor particularly for software developers to consider is efficiency in processing. UTF-32 has an advantage in that every character is exactly the same size, and there is never a need to test the value of a code unit to determine whether or not it is part of a sequence. Of course, this has to be weighed against considerations of the overall size of data, for which UTF-32 is generally quite inefficient. Also, while UTF-32 may allow for more efficient processing than UTF-16 or UTF-8, it should be noted that none of the three encoding forms is particularly inefficient with respect to processing. Certainly, it is true that all of them are much more efficient than are the various legacy multibyte encodings.

For general use with data that includes a variety of characters mostly from the BMP, UTF-16 is a good choice for software developers. BMP characters are all encoded as 16-bits, and testing for surrogates can be done very quickly. In terms of storage, it provides a good balance for multilingual data that may include characters from a variety of scripts in the BMP, and is no less efficient than other encoding forms for supplementary-plane characters. For these reasons, many applications that support Unicode use UTF-16 as the primary encoding form.

There are certain situations in which one of the other encoding forms may be preferred, however. In situations in which a software process needs to handle a single character (for example, to pass a character generated by a keyboard driver to an application), it is simplest to handle a single UTF-32 code unit. On the other hand, in situations in which software has to cooperate with existing implementations that were designed for 8-bit data only, then UTF-8 may be a necessity. UTF-8 has been most heavily used in the context of the Internet for this reason.

On first consideration, it may appear that having three encoding forms would be less desirable. In fact, having three encoding forms based on 8-, 16- and 32-bit code units has provided considerable flexibility for developers and has made it possible to begin making a transition to Unicode while maintaining operability with existing implementations. This has been a key factor in making Unicode a success within industry.

There is another related question worth considering here: Given a particular software product, which encoding form does it support? Some software may be able to handle “16-bit” Unicode data. Note, however, that this may actually mean UCS-2 data and not UTF-16; in other words, it is able to handle characters in the BMP, but not supplementary-plane characters encoded as surrogate pairs.

The question of support for supplementary-plane characters does not necessarily apply only to UTF-16. For example, many Web browsers are able to interpret HTML pages encoded in UTF-8, but that does not necessarily mean that they can handle supplementary-plane characters. For example, the software may convert data in the incoming file into 16-bit code units for internal processing, and that processing may not have been written to deal with surrogates correctly. Or, that application may have been written with proper support for supplementary-plane characters, but may depend on the host operating system for certain processing, and the host operating system on a given installation may not have the necessary support.

In general, when choosing software, you should verify whether it supports the encoding forms you would like to use. For both UTF-8 and UTF-16, you should explicitly verify whether the software is able to support supplementary-plane characters, if that is important to you.

Byte order: Unicode encoding schemes

Section titled “Byte order: Unicode encoding schemes”As explained in “Character set encoding basics”, 16- and 32-bit encoding forms raise an issue in relation to byte ordering. While code units may be larger than 8-bits, many processes are designed to treat data in 8-bit chunks at some level. For example, a communication system may handle data in terms of bytes, and certainly memory addressing with personal computers is organized in terms of bytes. Because of this, when 16- or 32-bit code units are involved, these may get handled as a set of bytes, and these bytes must get put into a serial order before being transmitted over a wire or stored on a disk.

There are two ways to order the bytes that make up a 16- or 32-bit code unit. One is to start with the high-order (most significant) byte and end with the low-order (least significant) byte. This is often referred to as big-endian. The other way, of course, is the opposite, and is often referred to as little-endian. For 16- and 32-bit encoding forms, the specification of a particular encoding form together with a particular byte order is known as a character encoding scheme.

In addition to defining particular encoding forms as part of the Standard, Unicode also specifies particular encoding schemes. A distinction must be made between the actual form in which the data is organized (what it really is) versus how a process might describe the data (what gets said about it).

Clearly, for data in the UTF-16 encoding form, it can only be serialized in one of two ways. In terms of how it is actually organized, it must be either big-endian or little-endian. However, Unicode allows three ways in which the encoding scheme for the data can be described: big-endian, little-endian, or unspecified-endian. The same is true for UTF-32.

Thus, Unicode defines a total of seven encoding schemes:

- UTF-8

- UTF-16BE

- UTF-16LE

- UTF-16

- UTF-32BE

- UTF-32LE

- UTF-32

Note that the labels “UTF-8”, “UTF-16” and “UTF-32” can be used in two ways: either as encoding form designations or as encoding scheme designations. In most situations, it is either clear or irrelevant which is meant. There may be situations in which you need to clarify which was meant, however.

Before a software process can interpret data encoded using the UTF-16 or UTF-32 encoding forms, the question of byte order does need to be resolved. Clearly, then, it is always preferable to tag data using an encoding scheme designation that overtly indicates which byte order is used. As Unicode was being developed, however, it was apparent that there would be situations in which existing implementation did not provide a means to indicate the byte order. Therefore the ambiguous encoding scheme designations “UTF-16” and “UTF-32” were considered necessary.

When the ambiguous designators are applied, however, the question of byte order still has to be resolved before a process can interpret the data. One possibility is simply to assume one byte order, begin reading the data and then check to see if it appears to make sense. For example, if the data were switching from one script to another with each new character, you might suspect that it was not being interpreted correctly. This approach is not necessarily reliable, though some software vendors have developed algorithms that try to detect the byte order, and even the encoding form, and these algorithms work in most situations.

To solve this problem, the codepoint U+FEFF was designated to be a byte order mark (BOM). When encountered at the start of a file or data stream, this character can always make clear which byte order is being used. The reason is that the codepoint that would correspond to the opposite byte order, U+FFFE, is reserved as a non-character.

For example, consider a file containing the Thai text “ความจริง”. The first character “ค” THAI CHARACTER KHO KHWAI has a codepoint of U+0E04. Now, suppose that the file is encoded in UTF-16 and is stored in big-endian order, though the encoding scheme is identified ambiguously as “UTF-16”. Suppose, then, that an application begins to read the file. It encounters the byte sequence 0x0E 0x04, but has no way to determine whether to assume big-endian order or little-endian order. If it assumes big-endian order, it interprets these bytes as U+0E04 THAI CHARACTER KHO KHWAI; but if it assumes little-endian order, it interprets these bytes as U+040E CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER SHORT U. Only one of these interpretations is correct, but the software has no way to know which.

But suppose the byte order mark, U+FEFF, is placed at the start of the file. Thus, the first four bytes in sequence are 0xFE 0xFF 0x0E 0x04. Now, if the software attempts to interpret the first two bytes in little-endian order, it interprets them as U+FFFE. But that is a non-character and, therefore, not a possible interpretation. Thus, the software knows that it must assume big-endian order. Now it interprets the first four bytes as U+FEFF (the byte-order mark) and U+0E04 THAI CHARACTER KHO KHWAI, and it is assured of the correct interpretation.

It should be pointed out that the codepoint U+FEFF has a second interpretation: ZERO WIDTH NO-BREAK SPACE. Unicode specifies that if data is identified as being in the UTF-16 or UTF-32 encoding scheme (not form) so that the byte order is ambiguous, then the data should begin with U+FEFF and that it should be interpreted as a byte order mark and not considered part of the content. If the byte order is stated explicitly, using an encoding scheme designation such as UTF-16LE or UTF-32BE, then the data should not begin with a byte order mark. It may begin with the character U+FEFF, but if so it should be interpreted as a ZERO WIDTH NO-BREAK SPACE and counted as part of the content.

The use of the BOM works in exactly the same way for UTF-32, except that the BOM is encoded as four bytes rather than two.

Note that the BOM is useful for data stored in files or being transmitted, but it is not needed for data in internal memory or passed through software programming interfaces. In those contexts, a specific byte order will generally be assumed.

The byte order mark is often considered to have another benefit aside from specifying byte order: that of identifying the character encoding. In most if not all existing legacy encoding standards, the byte sequences 0xFE 0xFF and 0xFF 0xFE are extremely unlikely. Thus, if a file begins with this value, software can infer with a high level of confidence that the data is Unicode, and also be able to deduce the encoding form. This also applies for UTF-32, though in that case the byte sequences would be 0x00 0x00 0xFE 0xFF and 0xFF 0xFE 0x00 0x00. It is also applicable in the case of UTF-8. In that case, the encoded representation of U+FEFF is 0xEF 0xBB 0xBF.

When the BOM is used in this way to identify the character set encoding of the data, it is referred to as an encoding signature.

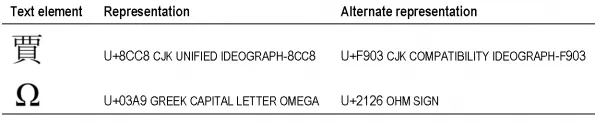

Compromises in the principle of unification

Section titled “Compromises in the principle of unification”The first type of duplication we will consider involves a simple violation of unification: Unicode has pairs of characters that are effectively one-for-one duplicates. For instance, U+212A KELVIN SIGN “K” was encoded as a distinct character from U+004B LATIN CAPITAL LETTER K because these were distinguished in some source standard; otherwise, there is no need to distinguish these in shape or in terms of how they are processed. The same situation applies to other pairs, such as U+212B ANGSTROM SIGN versus U+00C5 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A WITH RING ABOVE, and U+037E GREEK QUESTION MARK versus U+003B SEMICOLON.

In the source legacy standards, the two characters in a pair would have been assumed to have distinct functions. In these cases, however, the distinctions can be considered artificial. For example, in the case of the Kelvin sign and the letter K, there is no distinction in shape or in how they are to be handled by text processes. This is purely a matter of interpretation at a higher level. Distinguishing these would be like distinguishing the character “I” when used as an English pronoun from “I” used as an Italian definite article. This is not the type of distinction that needs to be reflected in a character encoding standard.

In TUS 3.1, there were over 800 exact duplicates for Han ideographs. These are located in the CJK Compatibility Ideographs (U+F900..U+FAFF) and the CJK Compatibility Ideographs Supplement (U+2F800..U+2FA1F) blocks. Note, however, that not every character in the former block is a duplicate. As the characters were being collected from various sources, these were prepared as a group and kept together. There are, in fact, twelve characters in this block that are unique and are not duplicates of any other character, such as U+FA0E 﨎 CJK COMPATIBILITY IDEOGRAPH-FA0E. Thus, you need to pay close attention to details in order to know what the status of any character is. In particular, you cannot assume that a character is a duplicate just because it is in the compatibility area of the BMP (U+F900..U+FFFF) or is from a block that has “compatibility” in the name.

Beyond the duplicate Han characters, there are another 33 of these singleton (one-to-one) duplicates in the lower end of the BMP, most of them in the Greek (U+0370..U+03FF) or Greek Extended (U+1F00..U+1FFF) blocks.

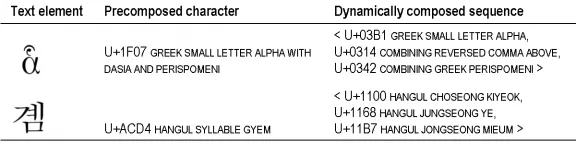

Compromises in the principle of dynamic composition

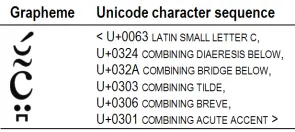

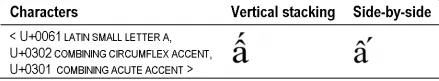

Section titled “Compromises in the principle of dynamic composition”The second type of duplication we will look at involves cases in which a character duplicates a sequence of characters. As described in Dynamic Composition, a text element may be represented as a combining character sequence. For instance, Latin a-circumflex with dot-below “ậ” can be represented as a sequence <U+0061 LATIN SMALL LETTER A, U+0323 COMBINING DOT BELOW, U+0302 COMBINING CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT>. In such cases, it is assumed that an appropriate rendering technology will be used that can do the glyph processing needed to correctly position the combining marks. In many cases, however, legacy standards encoded precomposed base-plus-diacritic combinations as characters rather than composing these combinations dynamically. As a result, it was necessary to include precomposed characters such as U+1EAD ậ LATIN SMALL LETTER A WITH CIRCUMFLEX AND DOT BELOW in Unicode.

Unicode has a very large number of precomposed characters, including 730 for Greek and Latin, and over 11,000 for Korean! Most of the Latin Extended Additional (U+1E00..U+1EFF) and the Greek Extended (U+1F00..U+1FFF) blocks and the entire Hangul Syllables block (U+AC00..U+D7AF) are filled with precomposed characters. There are also over 200 precomposed characters for Japanese, Cyrillic, Hebrew, Arabic and various Indic scripts.

Not all of the precomposed characters are from scripts used in writing human languages. There are a few dozen precomposed mathematical operators; for example, U+2260 NOT EQUAL TO, which can also be represented as the sequence <U+003D EQUALS SIGN, 0338 COMBINING LONG SOLIDUS OVERLAY>. There are also 13 precomposed characters for Western musical symbols in Plane 1; for example U+1D15F MUSICAL SYMBOL QUARTER NOTE, which can also be represented as the sequence <U+1D158 MUSICAL SYMBOL NOTEHEAD BLACK, U+1D165 MUSICAL SYMBOL COMBINING STEM>.

Precomposed characters go against the principle of dynamic composition, but also against the principle that Unicode encodes abstract characters rather than glyphs. In principle, it should be possible for a combining character sequence to be rendered so that the glyphs for the combining marks are correctly positioned in relation to the glyph for the base, or even so that the character sequence is translated into a single precomposed glyph. In these cases, though, that glyph is directly encoded as a distinct character.

There are other cases in which the distinction between characters and glyphs is compromised. Those cases have some significant differences from the ones we have considered thus far. Before continuing, though, there are some important additional points to be covered in relation to the characters described in Compromises in the principle of unification and Compromises in the principle of dynamic composition. We will return to look at the remaining areas of compromise in Compromises in the distinction between characters and glyphs.

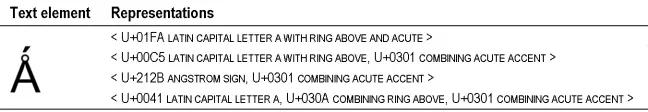

Canonical equivalence and the principle of equivalent sequences

Section titled “Canonical equivalence and the principle of equivalent sequences”There are thousands of instances of the situations described in Compromises in the principle of unification and Compromises in the principle of dynamic composition. In each of these cases, Unicode provides alternate representations for a given text element. For singleton duplicates, what this means is that there are two codepoints that are effectively equivalent and mean the same thing:

Likewise in the case of each precomposed character, there is a dynamically composed sequence that is equivalent and means the same thing as the precomposed character:

This type of ambiguity is far from ideal, but was a necessary price of maintaining backward compatibility with source standards and, specifically, the round-trip rule. In view of this, one of the original design principles of Unicode was to allow for a text element to be represented by two or more different but equivalent character sequences.

In these situations, Unicode formally defines a relationship of canonical equivalence between the two representations. Essentially, this means that the two representations should generally be treated as if they were identical, though this is slightly overstated.

In precise terms, the Unicode Standard defines a conformance requirement in relation to canonically equivalent pairs that must be observed by software that claims to conform to the Standard:

Conformance requirement 9. A process shall not assume that the interpretations of two canonical-equivalent character sequences are distinct.

In other words, software can treat the two representations as though they were identical, but it is also allowed to distinguish between them; it just cannot always treat them as distinct.

Since the different sequences are supposed to be equal representations of exactly the same thing, it might seem that this requirement is stated somewhat weakly, and that it ought to be appropriate to make a much stronger requirement: software must always treat canonical-equivalent sequences identically. Most of the time, it does make sense for software to do that, but there may be certain situations in which it is valid to distinguish them. For example, you may want to inspect a set of data to determine if any precomposed characters are used. You could not do that if precomposed characters are never distinguished from the corresponding dynamically composed sequence.

At this point, we can introduce some convenient terminology that is conventionally used. Whereas a character like U+1EAD LATIN SMALL LETTER A WITH CIRCUMFLEX AND DOT BELOW is referred to as a precomposed character, the corresponding combining character sequence <U+0061 LATIN SMALL LETTER A, U+0323 COMBINING DOT BELOW, U+0302 COMBINING CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT> is often referred to as a decomposed representation or a decomposed character sequence. The formal relationship between a precomposed character and the equivalent decomposed sequence is formally known as canonical decomposition. These mappings are specified as part of the semantic character properties contained in the online data files that were mentioned in Where the character properties are listed and described is said to be the canonical decomposition of U+212B ANGSTROM SIGN.

In some cases a text element can be represented as either fully composed or fully decomposed sequences. In many cases, however, there will be more than just these two representations. In particular, this can occur if there is a precomposed character that corresponds to a partial representation of another text element. For example, a text element a-ring-acute “Ǻ” can be represented in Unicode using fully composed or fully decomposed representation, but also using a partially decomposed representation:

Thus, in this example, there are four possible representations that are all canonically equivalent to one another. We will look at the possibility of having multiple equivalent representations further in Stacking of non-spacing combining marks.

There is more to be explained regarding the relationship between canonical-equivalent sequences, and we will be looking at further details in Other rendering behaviours, Combining marks and canonical ordering, Normalization, and Deciding how to encode data. Before returning to discuss ways in which Unicode design principles have been compromised, there are some specific points worth mentioning regarding certain characters for vowels in Indic scripts.

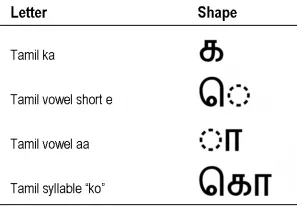

Indic scripts have combining vowel marks that can be written above, below, to the left or to the right of the syllable-initial consonant. In many Indic scripts, certain vowel sounds are written using a combination of these marks, as illustrated in the figure below:

Such combinations are especially typical in representing the sounds “o” and “au” using combinations of vowel marks corresponding to “e”, “i” and “a”.

What is worth noting is that these vowels are not handled in the same way in Unicode for all Indic scripts. In a number of cases, Unicode includes characters for the precomposed vowel combination in addition to the individual vowel signs. This happens for Bengali, Oriya, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Sinhala, Tibetan and Myanmar scripts. Thus, for example, in Tamil one can use U+0BCA ொ TAMIL VOWEL SIGN O or the sequence <U+0BC6 TAMIL VOWEL SIGN E, U+0BBE TAMIL VOWEL SIGN AA>. On the other hand, in Thai and Lao, the corresponding vowel sounds can only be represented using the individual component vowel signs. Thus in Thai, the syllable “kau” can only be represented as <U+0E40 THAI CHARACTER SARA E, U+0E01 THAI CHARACTER KO KAI, U+0E32 THAI CHARACTER SARA AA>. Then again, in Khmer, only precomposed characters can be used. Thus in Khmer, the corresponding vowel is represented using U+17C5 ៅ KHMER VOWEL SIGN AU; Unicode does not include characters for both of the component marks, and so there is no alternate representation. If you need to encode data, therefore, for a language that uses an Indic script, pay close attention to how that particular script is supported in Unicode.

Compromises in the distinction between characters and glyphs

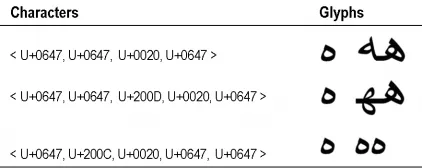

Section titled “Compromises in the distinction between characters and glyphs”Returning to our discussion of compromises in the design principles, the next cases we will look at blur the distinction between characters and glyphs. As explained earlier, Unicode assumes that software will support rendering technologies that are capable of the glyph processing needed to handle selection of contextual forms and ligatures. Such capability was not always available in the past, however. The result is that Unicode includes a number of cases of presentation forms—glyphs that are directly encoded as distinct characters but that are really only rendering variants of other characters or combinations of characters. For example, U+FB01 fi LATIN SMALL LIGATURE FI encodes a glyph that could otherwise be represented as a sequence of the corresponding Latin characters.

There are five blocks in the compatibility area that primarily encode presentation forms. Two of these are the Arabic Presentation Forms-A block (U+FB50..U+FDFF) and the Arabic Presentation Forms-B block (U+FE70..U+FEFF). These blocks mostly contain characters that correspond to glyphs for Arabic ligatures and contextual shapes that would be found in different connective relationships with other glyphs (initial, medial, final and isolate forms). So, for example, U+FEEC ﻬ ARABIC LETTER HEH MEDIAL FORM encodes the glyph that would be used to present the Arabic letter heh (nominally, the character U+0647 ARABIC LETTER HEH) when it is connected on either side. Unicode includes 730 such characters for Arabic presentation forms.

Characters like this constitute duplicates of other characters. There is a difference between this situation and that described in Compromises in the principle of unification and Compromises in the principle of dynamic composition, however. In the case of the singleton duplicates, the two characters were, for all intents and purposes, identical: in principle, they could be exchanged in any situation without any impact on text processing or on users. Likewise for the precomposed characters and the corresponding (fully or partially) decomposed sequences. In the case of the Arabic presentation forms, though, they are equivalent only in certain rendering contexts. For example, U+FEEC could not be considered equivalent to a word-initial occurrence of U+0647. For situations like this, Unicode defines a lesser type of equivalence known as compatibility equivalence: two characters are in some sense duplicates but with some limitations and not necessarily in all contexts. Formally, the compatibility equivalence relationship between two characters is shown in a compatibility decomposition mapping that is part of the Unicode character properties. The relationship between compatibility equivalence and canonical equivalence are discussed in (De)Composition and Normalization.

In general, use of the characters in the Arabic Presentation Forms blocks is best avoided whenever possible. Note, though, that these blocks contain three characters that are unique characters and are not duplicates of any others: U+FD3E ﴾ ORNATE LEFT PARENTHESIS, U+FD3F ﴿ ORNATE RIGHT PARENTHESIS and U+FEFF ZERO WIDTH NO-BREAK SPACE. As we saw earlier, you need to check the details on characters in the Standard before you make assumptions about them.

The other three blocks that contain primarily presentation forms are the Alphabetic Presentation Forms block (U+FB00..U+FB4F), the CJK Compatibility Forms block (U+FE30..U+FE4F), and the Combining Half Marks block (U+FE20..U+FE2F). The first of these contains various Latin, Armenian and Hebrew ligatures, such as the “fi” ligature mentioned above. This block also has wide variants of certain Hebrew letters, which were used in some legacy systems for justification of text, and two Hebrew characters that are no more than font variants of existing characters. The CJK Compatibility Forms block contains rotated variants of various punctuation characters for use in vertical text; for example, U+FE35 ︵ PRESENTATION FORM FOR VERTICAL LEFT PARENTHESIS. Finally, the Combining Half Marks block contains presentation forms representing the left and right halves of glyphs for diacritics that span multiple base characters; for example, U+FE22 ︢ COMBINING DOUBLE TILDE LEFT HALF and U+FE23 ︣ COMBINING DOUBLE TILDE RIGHT HALF. These are not variants of other characters or sequences of characters. Rather, pairs of these are variants of other characters. Unicode does not formally define any type of equivalence that covers such situations.

Outside the compatibility area at the top of the Basic Multilingual Plane, there are no characters for contextual presentation forms (like the Arabic positional variants), and there are but a handful of ligatures, such as U+0587 և ARMENIAN SMALL LIGATURE ECH YIWN, and U+0EDC ໜ LAO HO NO.

Compromises in the distinction between characters and graphemes

Section titled “Compromises in the distinction between characters and graphemes”The next category of compromise has to do with the distinction between characters and graphemes. In particular, Unicode includes some characters for Latin digraphs. For example, U+01F2 Dz LATIN CAPITAL LETTER D WITH SMALL LETTER Z and U+1E9A ẚ LATIN SMALL LETTER A WITH RIGHT HALF RING. Most of these are to be found in the Latin Extended-B block (U+0180..U+024F). Others are in the Latin Extended-A block (U+0100..U+017F), and there is one (U+1E9A) in the Latin Extended Additional block (U+1E00..U+1EFF).

All of these digraphs are duplicates for sequences involving the corresponding pairs of characters. In each case, Unicode designates the digraph character to be a compatibility equivalent to the corresponding sequence.

Character Properties

Section titled “Character Properties”Character semantics and behaviours

Section titled “Character semantics and behaviours”Software creates the impression of understanding the behaviours of writing systems by attributing semantic character properties to encoded characters. These properties represent parameters that determine how various text processes treat characters. For example, the SPACE character needs to be handled differently by a line-breaking process than, say, the U+002C COMMA character. Thus, U+0020 SPACE and U+002C COMMA have different properties with respect to line-breaking.

One of the distinctive strengths of Unicode is that the Standard not only defines a set of characters, but also defines a number of semantic properties for those characters. Unicode is different from most other character set encoding standards in this regard. In particular, this is one of the key points of difference between Unicode and ISO/IEC 10646.

In addition to the semantic properties, Unicode also provides reference algorithms for certain complex processes for which the correct implementation may not be self evident. In this way, the Standard is not only defining semantics properties for characters, but is also guiding how semantics should be interpreted. This has an important benefit for users in that it leads to more consistent behaviour between software implementations. There is also a benefit for software developers who are suddenly faced with supporting a wide variety of languages and writing systems: they are provided with important information regarding how characters in unfamiliar scripts behave.

It is important that characters are used in a way that is consistent with their properties

Where the character properties are listed and described

Section titled “Where the character properties are listed and described”The character properties and behaviours are listed and explained in various places, including the Unicode Core Specification, some of the technical reports and annexes, and in online data files. An obvious starting point for information on character properties is Chapter 4 of TUS. That chapter describes or lists some of the properties directly, and otherwise indicates the place in which many other character properties are covered.

The complete listing of character properties is given in the data files that comprise the Unicode Character Database (UCD). These data files are available online. A complete reference regarding the files that make up the UCD and the place in which each is described is provided in the document at UnicodeCharacterDatabase.html.

The original file that contained the character properties is UnicodeData.txt. This is considered the main file in the UCD and is one that is perhaps most commonly referred to. It is just one of several, however. This file was first included as part of the Standard in Version 1.1.5. Like all of the data files, it is a machine readable text database. As new properties were defined, additional files were created. This was done rather than adding new fields to the original file in order to remain compatible with software implementations designed to read that file.

Normative versus informative properties and behaviours

Section titled “Normative versus informative properties and behaviours”Unicode distinguishes between normative properties and informative properties. Software that conforms to Unicode is required to observe all normative properties. The informative properties are provided as a guide, and it is recommended that software developers generally follow them, but implementations may override those properties while still conforming to the Standard. All of the properties are defined as part of the Standard, but only the normative properties are required to be followed.

One reason for this distinction is that some properties are provided for documentation purposes and have no particular relevance for implementations. For example, the Unicode 1.0 Name property is provided for the benefit of implementations that may have been based on that version. Another similar property is the 10646 comment property, which records notes from that standard consisting primarily of alternate character names and the names of languages that use that character. Another example is the informative notes and cross-references in NamesList.txt, which provide supplementary information about characters that is helpful for readers in identifying and distinguishing between characters.

Another reason for the distinction is that it may not be considered necessary to require certain properties to be applied consistently across all implementations. This would apply, for instance, in the case of a property that is not considered important enough to invest the effort in giving careful thought to the definition and assignment of the property for all characters. For example, the kMainlandTelegraph property identifies the telegraph code used in the People’s Republic of China that corresponds to a given unified Han character. This property may be valuable in some contexts, but is not likely to be something that is felt to need normative treatment within Unicode.

For some properties, it may also be considered inappropriate to impose particular requirements on conformant implementations. This might be the case if it is felt that a given category of processes is not yet well enough understood to specify what the normative behaviour for those processes should be. For example, Line Breaking properties are defined in Unicode for each character, and they reflect what are considered to be best practices to the extent that line breaking is understood. The treatment of line breaking properties is thought to largely reflect best practices that are valid for many situations, but is not considered to have completely covered all aspects of line breaking behaviour. Current knowledge regarding line breaking is not complete enough to make a complete and normative specification of line breaking behaviour that becomes a conformance requirement on software. As a result, some line breaking properties are normative—for instance, a break is always allowed after a ZERO-WIDTH SPACE and is always mandatory after a CARRIAGE RETURN—but most line-breaking properties are informative and can be modified in a given implementation.

It is also inappropriate to impose normative requirements in the case of properties for which the status of some characters is controversial or simply unclear. For example, a set of case-related properties exist that specify the effective case of letter-like symbols. For instance, U+24B6 Ⓐ CIRCLED LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A is assigned the Other_Uppercase property. For some symbols, however, it is unclear what effective case they should be considered to have. The character U+2121 ℡ TELEPHONE SIGN, for instance, has been realized using a variety of glyphs. Some glyphs use small caps while others use all caps. It is difficult to have any confidence in making a property such as Other_Uppercase normative when the status of some characters in relation to that property is unclear.

The normative and informative distinction applies to the specification of behaviours as well as to character properties. For example, UAX #9 describes behaviour with regard to the layout of bi-directional text (the “bi-directional algorithm”) and that behaviour is a normative part of the Standard. Likewise, the properties in ArabicShaping.txt (described in The Unicode Core Specification, Chapter 9) that describe the cursive shaping behaviour of Arabic and Syriac characters are also normative. On the other hand, UAX #14 describes an algorithm for processing the line breaking properties, but that algorithm is not normative. Similarly, Section 5.12 of TUS discusses the handling of non-spacing combining marks in relation to processes such as keyboard input, but the guidelines it presents are informative only.

There is one other point that is important to note in relation to the distinction between normative and informative properties: the fact that a property is normative does not imply that it can never change. Likewise, the fact that a property is informative does not imply that it is open to change. For example, the Unicode 1.0 Names property is informative but is not subject to change. On the other hand, several changes were made in TUS 3.0 to the Bi-directional Category, Canonical Combining Class and other normative properties in order to correct errors and refine the specification of behaviours. As a rule, though, it is the case that changes to normative properties are avoided, and that some informative properties can be more readily changed.

It is also true that some normative properties are not subject to change. In particular, the Character name property is not permitted to change, even in cases in which, after the version of the Standard in which a character is introduced is published, the name is found to be inappropriate. The reason for this is that the sole purpose of the character name is to serve as a unique and fixed identifier.

A summary of significant properties

Section titled “A summary of significant properties”The properties that are probably most significant are those found in the main character database file, UnicodeData.txt.

The format for the UnicodeData.txt file is described in UAX #44. UnicodeData.txt is a semicolon-delimited text database with one record (i.e. one line) per character. There are 15 fields in each record, each field corresponding to a different property. All of the properties in this file apart from the Unicode 1.0 Name and 10646 comment (described above) are normative.

The first field corresponds to the codepoint for a given character, the significance of which is obvious. The next field contains the character name, which provides a unique identifier in addition to the codepoint. There is an importance to the character name as an identifier over the codepoint in that, while the codepoint is applicable only to Unicode, the character name may be constant across a number of different character set standards, facilitating comparisons between standards.

The next field contains the General Category properties. This categorises all of the characters into a number of useful character types: letter, combining mark, number, punctuation, symbol, control, separator, and other. Each of these is further divided into subcategories. Thus, letters are designated to be uppercase, lowercase, or titlecase. Each of these subcategories is indicated in the data file using a two-letter abbreviation. The complete list of general category properties and their abbreviations is listed in Table 2:

| Cc | Other, Control | No | Number, Other |

| Cf | Other, Format | Pc | Punctuation, Connector |

| Cn | Other, Not Assigned | Pd | Punctuation, Dash |

| Co | Other, Private Use | Pe | Punctuation, Close |

| Cs | Other, Surrogate | Pf | Punctuation, Final quote |

| Ll | Letter, Lowercase | Pi | Punctuation, Initial quote |

| Lm | Letter, Modifier | Po | Punctuation, Other |

| Lo | Letter, Other | Ps | Punctuation, Open |

| Lt | Letter, Titlecase | Sc | Symbol, Currency |

| Lu | Letter, Uppercase | Sk | Symbol, Modifier |

| Mc | Mark, Spacing Combining | Sm | Symbol, Math |

| Me | Mark, Enclosing | So | Symbol, Other |

| Mn | Mark, Non-Spacing | Zl | Separator, Line |

| Nd | Number, Decimal Digit | Zp | Separator, Paragraph |

| Nl | Number, Letter | Zs | Separator, Space |

Table 2: General category properties and their abbreviations

This set of properties forms a partition of the Unicode character set; that is, every character is assigned exactly one of these general category properties.

Space does not permit a detailed description of all of these properties. General information can be found in Chapter 4.5 of the Unicode Core Specification. Some of these properties are not discussed in detail in the Standard using these explicit names, so information may be difficult to find. For some of the properties, it may be more likely to find information about individual characters than about the groups of characters as a whole. Many of these categories are significant in relation to certain behaviours, though. Several are discussed in Chapter 5 of TUS. Many of them are particularly relevant in relation to line breaking behaviour, described in UAX #14.

The control, format and other special characters are discussed in Chapter 23 of TUS. Numbers are described in Chapter 22 and in most of the various sections covering different scripts in Chapters 7–20. Punctuation and spaces are discussed in Chapter 6 of TUS. Symbols are the topic of Chapter 22 of TUS. Line and paragraph separators are covered in Chapter 5.

It will be worth describing letters and case in a little more detail, and we will do so after finishing this general survey of character properties. Combining marks will also be discussed.

Returning to our discussion of the fields in the UnicodeData.txt database file, the fourth, fifth and sixth fields contain particularly important properties: the Canonical Combining Classes, Bi-directional Category and Decomposition Mapping properties. Together with the general category properties, these three properties are the most important character properties defined in Unicode. Accordingly, each of these will be given additional discussion. The canonical combining classes are relevant only for combining marks (characters with general category properties of Mn, Mc and Me), and will be described in more detail in Combining marks and canonical ordering. The bi-directional categories are used in relation to the bi-directional algorithm, which is specified in UAX #9. A brief outline of this is provided in Rendering Behaviors. Finally, the character decomposition mappings specify canonical and compatibility equivalence relationships. We will discuss this further in (De)Composition and Normalization.

Most of the next six fields contain properties that are of more limited significance. Fields seven to nine relate to the numeric value of numbers (characters with general category properties (Nd, Nl and No)). These are covered in Section 4.6 of TUS. The tenth field contains the Mirrored property, which is important for right-to-left scripts, and is described in Section 4.7 of TUS and also in UAX #9 (the bi-directional algorithm). I will say more about it in Rendering Behaviors. Fields eleven and twelve contain the Unicode 1.0 Name and 10646 properties.

The last three fields contain case mapping properties: Uppercase Mapping, Lowercase Mapping, and Titlecase mapping. These are considered further in Case Mappings.

As mentioned earlier, UnicodeData.txt is a semicolon-delimited text database. Now that each of the fields have been described, here are some examples:

0028;LEFT PARENTHESIS;Ps;0;ON;;;;;Y;OPENING PARENTHESIS;;;;0031;DIGIT ONE;Nd;0;EN;;1;1;1;N;;;;;0061;LATIN SMALL LETTER A;Ll;0;L;;;;;N;;;0041;;00410407;CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER YI;Lu;0;L;0406 0308;;;;N;;Ukrainian ;;0457;Note that not every field necessarily contains a value. For example, there is no uppercase mapping property for U+0028. Every entry in this file contains values, however, for the following fields: codepoint, character name, general category, canonical combining class, bi-directional category, and mirrored.

Looking at the first of these entries, we see that U+0028 has a general category of “Ps” (opening punctuation—see Table 2), a canonical combining class of “0”, a bi-directional category of “ON”, and a mirrored property of “Y”. It also has a Unicode 1.0 name of “OPENING PARENTHESIS”.

The entry for U+0031 shows a general category of “Nd” (decimal digit number), a combining class of “0”, a bi-directional category of “EN”, and a mirrored property of “N”. Since this character is a number, fields seven to nine (having to do with numeric values) contain values, each of them “1”.

The character U+0061 has a general category of “Ll” (lowercase letter), a combining class of “0”, a bi-directional category of “L”, and a mirrored property of “N”. It also has uppercase and titlecase mappings to U+0041.

Finally, looking at the last entry, we see that U+0407 has a general category of “Lu” (uppercase letter), a combining class of 0, a bi-directional category of “L”, and a mirrored property of “N”. It also has a canonical decomposition mapping to < U+0406, U+0308 >, a 10646 comment of “Ukrainian”, and a lowercase mapping to U+0457.

UnicodeData.txt has been described the main file in the Unicode character database in some detail. There are a number of other files listing character properties in the Unicode character database. Some of the more significant files have been mentioned in earlier sections. Of the rest, it would be beyond the scope of an introduction to explain every one, and all of them are described in UAX #44. More details are give below on those that are most significant. In particular, additional properties related to case are discussed in Case Mappings together with a fuller discussion of the case-related properties mentioned in this section; and the properties listed in the ArabicShaping.txt and BidiMirroring.txt files will be described in Rendering Behaviors, together with further details on the mirrored property mentioned here.

Glyph Similarities

Section titled “Glyph Similarities”The Unicode Standard does not unify letter shapes or characters across scripts (unless those characters are common to all, for example combining diacritics). Thus there is both a Latin “A” (U+0041 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A) and a Cyrillic “А” (U+0410 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER A). A font supporting both Latin and Cyrillic scripts might use the exact same glyph to display both of these Unicode characters.

The existence of these “confusable” characters also offers the possibility of deliberate, malicious attempts to deceive users.

You will do your users a great service if your software can warn users when they use a character from a different script.

Additional resources:

- Dotless letters and movable combining marks

- Unicode Utilities: Confusables

- Unicode’s Where is my Character?

- Unicode Character Properties spreadsheet

Case Mappings

Section titled “Case Mappings”Case is an important property for characters in Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, Armenian, Georgian and a few other scripts. For these scripts, both upper- and lowercase characters are encoded. Because some Latin and Greek digraphs were included in Unicode, it was necessary to add additional case forms to deal with the situation in which a string has an initial uppercase character. Thus, for these digraphs there are upper-, lower- and titlecase characters; for example, U+01CA NJ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER NJ, U+01CB Nj LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH SMALL LETTER J, and U+01CC nj LATIN SMALL LETTER NJ. Likewise, there are properties giving uppercase, lowercase and title case mappings for characters. Thus, U+01CA has a lowercase mapping of U+01CC and a titlecase mapping of U+01CB.

Case has been indicated in Unicode by means of the general category properties “Ll”, “Lu” and “Lt”. These have always been normative character properties. Prior to TUS 3.1, however, case mappings were always informative properties. The reason was that, for some characters, case mappings are not constant across all languages. For example, U+0069 i LATIN SMALL LETTER I is always lower case, no matter what writing system it is used for, but not all writing systems consider the corresponding uppercase character to be U+0049 I LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I. In Turkish and Azeri, for instance, the uppercase equivalent to “i” is U+0130 İ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I WITH DOT ABOVE. The exceptional cases such as Turkish and Azeri were handled by special casing properties that were listed in a file created for that purpose: SpecialCasing.txt.

The SpecialCasing.txt file was also used to handle other special situations, in particular situations in which a case mapping for a character is not one-to-one. These typically involve encoded ligatures or precomposed character combinations for which the corresponding uppercase equivalent is not encoded. For example, U+01F0 ǰ LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH CARON is a lowercase character, and its uppercase pair is not encoded in Unicode as a precomposed character. Thus, the uppercase mapping for U+01F0 must map to a combining character sequence, <U+004A LATIN CAPITAL LETTER J, U+030C COMBINING CARON>. This mapping is given in SpecialCasing.txt.

Note that not all characters with case are given case mappings. For example, U+207F ⁿ SUPERSCRIPT LATIN SMALL LETTER N is a lowercase character (indicated by the general category “Ll”), but it is not given uppercase or titlecase mappings in either UnicodeData.txt or in SpecialCasing.txt. This is true for a number of other characters as well. Several of them are characters with compatibility decompositions, like U+207F, but many are not. In particular the characters in the IPA Extensions block are all considered lowercase characters, but many do not have uppercase counterparts.

In TUS 3.1, case mappings were changed from being informative to normative. The reason for the change was that it was recognized that case mapping was a significant issue for a number of processes and that it was not really satisfactory to have all case mappings be informative. Thus, the mappings given in UnicodeData.txt are now normative properties. Special casing situations are still specified in SpecialCasing.txt, but this file is now considered normative as well.

Note that UnicodeData.txt indicates the case of characters by means of the general categories “Ll”, “Lu” and “Lt”, and not by case properties that are independent of the “letter” category. There are instances, however, in which a character that does not have one of these properties should be treated as having case or as having case mappings. This applies, for example, to U+24D0 ⓐ CIRCLED LATIN SMALL LETTER A, which has an uppercase mapping of U+24B6 Ⓐ CIRCLED LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A but does not have a case property since it has a general category of “So” (other symbol). As an accident of history in the way that the general category was developed, case was applied to characters that are categorized as letters, but not to characters categorized as symbols. This made case incompatible with being categorized as a symbol, even though case properties should be logically independent of the letter/symbol categories.